[A poem to read while “working at home” during a pandemic]

By Joyce Carol Oates

August 20, 2012

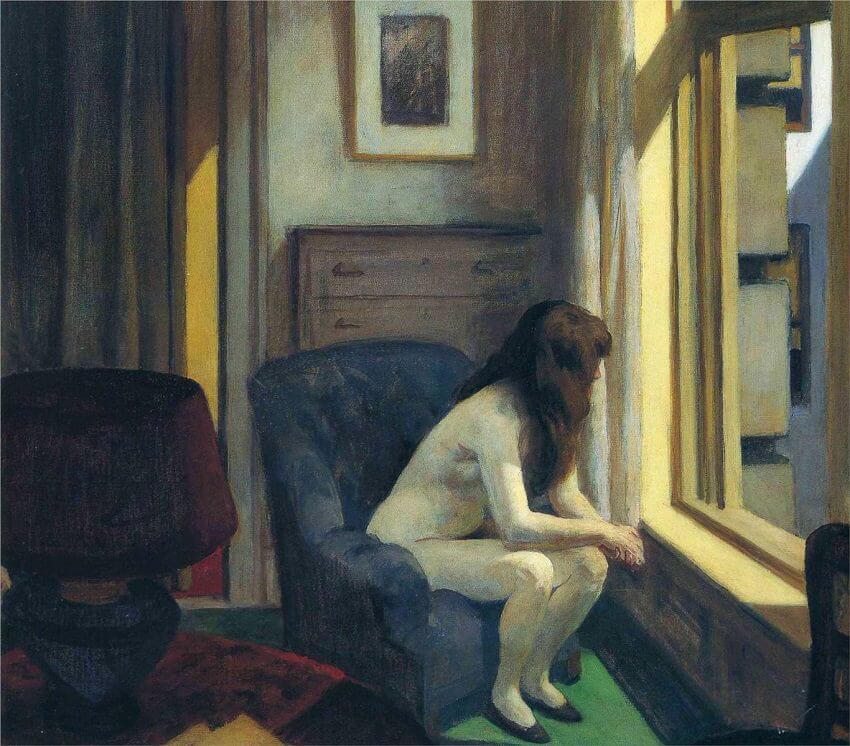

She’s naked yet wearing shoes.

Wants to think nude. And happy in her body.

Though it’s a fleshy aging body. And her posture

in the chair—leaning forward, arms on knees,

staring out the window—makes her belly bulge,

but what the hell.

What the hell, he isn’t here.

Lived in this damn drab apartment at Third Avenue,

Twenty-third Street, Manhattan, how many

damn years, has to be at least fifteen. Moved to the city

from Hackensack, needing to breathe.

She’d never looked back. Sure they called her selfish,

cruel. What the hell, the use they’d have made of her,

she’d be sucked dry like bone marrow.

First job was file clerk at Trinity Trust. Wasted

three years of her young life waiting

for R.B. to leave his wife and wouldn’t you think

a smart girl like her would know better?

Second job also file clerk but then she’d been promoted

to Mr. Castle’s secretarial staff at Lyman Typewriters. The

least the old bastard could do for her and she’d

have done a lot better except for fat-face Stella Czechi.

Third job, Tvek Realtors & Insurance and she’s

Mr. Tvek’s private secretary: What would I do

without you, my dear one?__

As long as Tvek pays her decent. And he doesn’t

let her down like last Christmas, she’d wanted to die.

This damn room she hates. Dim-lit like a region of the soul

into which light doesn’t penetrate. Soft-shabby old furniture

and sagging mattress like those bodies in dreams we feel

but don’t see. But she keeps her bed made

every God-damned day, visitors or not.

He doesn’t like disorder. He’d told her how he’d learned

to make a proper bed in the U.S. Army in 1917.

The trick is, he says, you make the bed as soon as you get up.

Detaches himself from her as soon as it’s over. Sticky skin,

hairy legs, patches of scratchy hair on his shoulders, chest,

belly. She’d like him to hold her and they could drift into

sleep together but rarely this happens. Crazy wanting her, then abruptly it’s over—he’s inside his head,

and she’s inside hers.

Now this morning she’s thinking God-damned bastard, this has

got to be the last time. Waiting for him to call to explain

why he hadn’t come last night. And there’s the chance

he might come here before calling, which he has done more than once.

Couldn’t keep away. God, I’m crazy for you.

She’s thinking she will give the bastard ten more minutes.

She’s Jo Hopper with her plain redhead’s face stretched

on this fleshy female’s face and he’s the artist but also

the lover and last week he came to take her

out to Delmonico’s but in this dim-lit room they’d made love

in her bed and never got out until too late and she’d overheard

him on the phone explaining—there’s the sound of a man’s voice

explaining to a wife that is so callow, so craven, she’s sick

with contempt recalling. Yet he says he has left his family, he

loves her.

Runs his hands over her body like a blind man trying to see. And

the radiance in his face that’s pitted and scarred, he needs her in

the way a starving man needs food. Die without you. Don’t

leave me.

He’d told her it wasn’t what she thought. Wasn’t his family

that kept him from loving her all he could but his life

he’d never told anyone about in the war, in the infantry,

in France. What crept like paralysis through him.

Things that had happened to him, and things

that he’d witnessed, and things that he’d perpetrated himself

with his own hands. And she’d taken his hands and kissed them,

and brought them against her breasts that were aching like the

breasts of a young mother ravenous to give suck,

and sustenance. And she said No. That is your old life.

I am your new life.

She will give her new life five more minutes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.